Ben Conlon

2016 winner of the Science for Development Award

"I really enjoyed the first time we visited a primary school near Lilongwe… [the children] wanted to play football and show us their games and dances. It was just a great experience, as well as being a bit harrowing when you saw the teacher to student ratio."

Project title: Preservation Of Water Supplies Using Hygroscopic Polymers

Category: Chemical, Physical & Mathematical Sciences

Overview: We plan on reducing the effects of evaporation on the scarce supplies of hot countries using hygroscopic polymers to form solid gels.

Ben won his prize as part of a group project while a Transition Year student at Salesian College Celbridge, Kildare. He is currently a final year student of Law at Trinity College Dublin.

Where did the initial idea for your project come from and how did it develop?

One of the team members of our project, Ruaidhrí Jordan, had become aware of the use of hygroscopic polymers in flooding - they were significantly more effective alternatives to sandbags because they absorbed massive amounts of water. At first, we were thinking about doing a project along the lines of flood defence, then we wondered how well the polymer retained water under heat. That thought led us to consider it as a possible solution to water scarcity around the world, which seems a lot worse now than it did in 2016, and it’s only been five years!

How did you go about researching the polymer’s effectiveness in preserving water?

Our experiments involved putting samples of hygroscopic polymers under a heat lamp for increasing periods of time, and regularly weighing the sample to see if water had dissipated from it, and our results showed it could hold on pretty strong. Most of the project was based on the experiment in the school lab, and some wider research into alternative ways of storing water.

You wanted to apply the property of water retention to the issue of water scarcity. Were you specifically looking at poorer countries prone to drought, or its more general usefulness?

At the time we were thinking it could be very useful in a lot of places. There had been some research done at the time about how you could take this polymer and put it in soil as a form of irrigation. We definitely thought it could be used in arid parts of the world that are wealthier but intended that the main use would be in the Global South to address issues of water retention.

Did you investigate the cost and accessibility for countries in the Global South as a part of your research?

We had a rough idea of the costs at the time, but it was the judging process at the BTYSTE that slowly pushed us more and more towards these obstacles and considering ways around them. Because sodium polyacrylate is a light substance, it can be transported very far for very little money, and it doesn’t take a lot of infrastructure to install. We lent heavily on the proposition of being able to source funding for humanitarian aid to get the water to people in emergency situations, rather than trying to provide finance for its everyday use.

You used a heat lamp to conduct your experiments and collect data. Did you find this a suitable method, or would you change how you did your research?

I think at the end of the day, the only way to get a strong, definitive answer would be to conduct the experiment in the exact location and conditions, and measure it over a number of months, rather than the small scale we were able to work with.

Did you encounter any challenges in your preparation for the Exhibition?

Being forced to develop the project beyond what we initially thought… We needed to think about how to use the positive results we had found and make what we learned useful in a practical way. How you turn this polymer back into water is by adding salt, after which you are left with a body of water and slush at the end, but we had to get the water to a potable state to be distributed to communities.

That led us to think about the potential to make use of what was causing the problem - the heat. We proposed that maybe the heat could be utilised for a greenhouse-like effect to separate the salt from the water and ultimately bring it to a clean state. However, that wasn’t part of our original idea or research, it was only after we had conducted the experiment that we had to think more expansively.

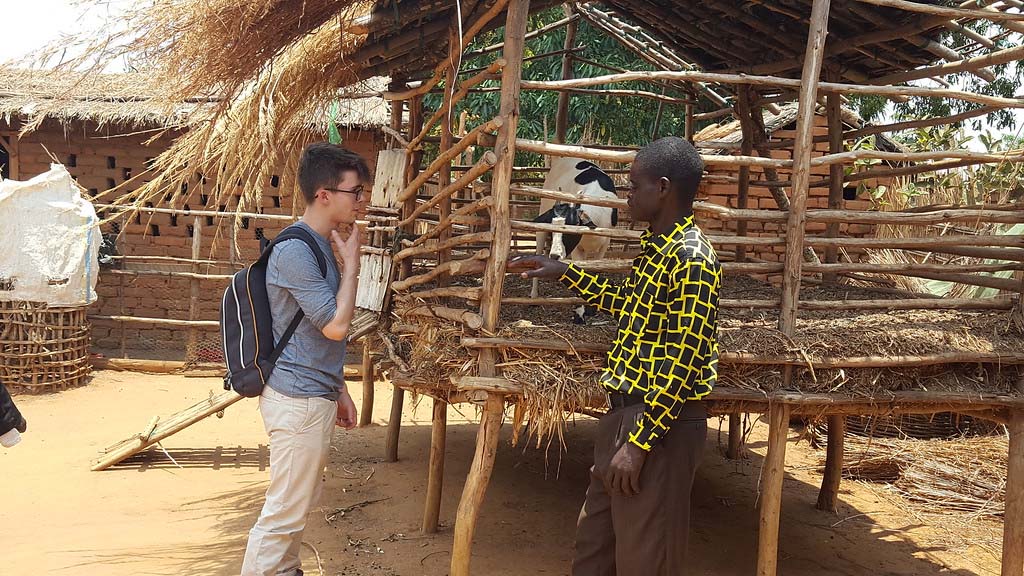

You went to Malawi for your study visit in 2016. Were there any differences in your expectations of the trip and the reality?

My experience contrasted with what our media has exposed us to. Growing up I had always seen ads on TV with very depressing depictions of many parts of the world. While they may not have the level of luxury, security, or development that we have, the people of Malawi still find a lot of meaning and joy in their lives despite very difficult circumstances and have such a rich culture. That had a massive impact on me. It’s nice to see that media portrayals have toned down in recent years, it’s such an important change to represent people in an authentic and realistic way.

What was your favourite part of the week?

I really enjoyed the first time we visited a primary school near Lilongwe, because when we got there all the kids of the school were outside, and they were all singing, running up to the bus and very excited to see everyone. They wanted to play football and show us their games and dances. It was just a great experience, as well as being a bit harrowing when you saw the teacher to student ratio.

You’re in the final year of your law degree - science and law wouldn’t be the most obvious pairing, but have you found any connections with your studies and Science for Development?

Yes, in relation to agreements between countries related to climate change, public international law would deal with this. However, the funny thing about those agreements is that a country is only bound to it up until they decide that they’re not! It’s not as effective as it appears when lots of countries have committed to do something. They are more like suggestions and guidelines, as they’re not valid until all signatories have ratified them, and no country is bound until that’s happened.

Your knowledge must be useful in understanding what these agreements mean and enable you to look at them critically. You’re also a managing editor of the Trinity College Law Review, can you tell us more about this publication, and what opportunities there are for students to get involved?

It’s the oldest student submission and student-edited law journal in Ireland. We have a print journal of long form pieces published annually around March. A number of partners sponsor prizes for various categories each year, for example, a senior counsel barrister sponsors a prize for the best article on public policy, and a firm sponsors the best legal technology article.

We also have an online version - TrinityCollegeLawReview.org - for shorter form blogs posted monthly. We run two competitions here annually: an alternative perspectives piece for a non-law student to write about how their field interacts with the law, and a Secondary Schools competition with titles provided. The winning articles are published on the blog.