Countries in southern Africa have endured both severe and destructive tropical storms, extreme flooding and successive years of drought in recent times.

Scientists link these events to a climatic phenomenon happening thousands of miles away in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, with a warming of sea surface temperature and changes to air pressure and atmospheric conditions known as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) blamed for some of southern Africa’s extreme weather events.

Although there is no definitive agreement in the scientific community on how climate change impacts El Niño, what isn’t in dispute is that weather conditions across the region are getting more extreme and unpredictable, and small-scale food producers are bearing the brunt.

Cyclone Idai caused extensive flooding, claiming hundreds of lives and leaving tens of thousands of families homeless in Mozambique in March 2019. The clean-up operation from this event had barely started when Cyclone Kenneth swept across the region, just six weeks later.

This was followed in early 2023 by Tropical Cyclone Freddy, which swept through Madagascar, Mozambique and Malawi, causing further devastation.

Meanwhile, the failure of seasonal rains in regions of Zambia as a result of the El Niño event has caused poor yields and, in some places, complete crop failure of the household food staple maize in recent years.

El Niño was forecasted in late 2023, so Self Help Africa was able to warn farmers and agricultural businesses well in advance and provide recommendations to mitigate the drought risks. These businesses stocked drought-tolerant and quick-maturing varieties, and those farmers who planted sorghum, pearl millet and cowpeas instead of maize achieved a reasonable harvest.

In Zambia, many farmers responded favourably to a Government campaign that contributed towards replenishing national stocks of maize, prompting farmers to plant the crop, which later failed across most of the southern half of the country.

By early 2024, the prolonged drought had reportedly affected 84 of Zambia’s 116 districts, destroying nearly half of the country’s maize crops (about one million hectares). A state of emergency was declared in late February, with estimates indicating that 5.8 million people (33 per cent of the population) may face acute food insecurity between October 2024 and March 2025. Among them, 236,000 people are expected to reach Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) Phase 4 (emergency) while 5.6 million people may be in IPC Phase 3 (crisis).

Despite efforts to protect families from extreme weather, resource-poor farming households have limited adaptative capacity.

To enable communities to better anticipate shocks, Self Help Africa invested in rain gauges, river flow gauges and automatic weather stations to improve the accuracy of early warning systems (EWS). Over 190 manual and automatic weather stations and seven river-line gauges to monitor river levels have been installed across Self Help Africa programmes in primary schools and at community centres in Malawi and Zambia. These activities contribute to both wider national weather data collection, while also providing local communities with earlier warning of imminent weather changes.

El Niño and La Niña. What are they?

During normal conditions in the Pacific Ocean, trade winds blow west along the equator, taking warm water from South America towards Asia. To replace that warm water, cold water rises from the depths.

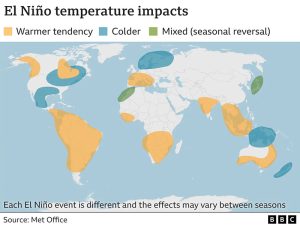

El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that break these normal conditions. Scientists call these phenomena the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. El Niño and La Niña can both have global impacts on weather, wildfires, ecosystems and economies. Episodes of El Niño and La Niña typically last nine to 12 months, but can sometimes last for years. El Niño and La Niña events occur every two to seven years, on average, but they don’t occur on a regular schedule. Generally, El Niño occurs more frequently than La Niña.

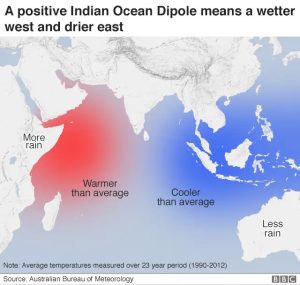

Indian Ocean Dipole

During normal conditions in the Pacific Ocean, trade winds blow west along the equator, taking warm water from South America towards Asia. To replace that warm water, cold water rises from the depths.

El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that break these normal conditions. Scientists call these phenomena the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. El Niño and La Niña can both have global impacts on weather, wildfires, ecosystems and economies. Episodes of El Niño and La Niña typically last nine to 12 months, but can sometimes last for years. El Niño and La Niña events occur every two to seven years, on average, but they don’t occur on a regular schedule. Generally, El Niño occurs more frequently than La Niña.